This reading covers:

A stakeholder is any individual or group that has a vested interest in a company. The primary stakeholder groups of a company include:

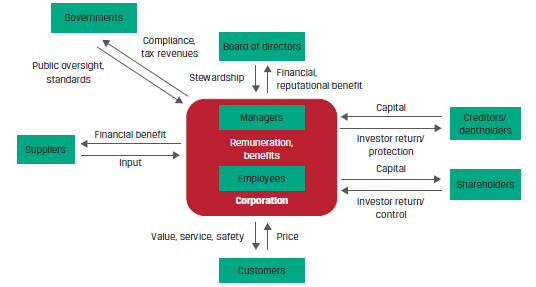

Exhibit 1 from the curriculum illustrates these relationships.

Traditional corporate governance frameworks were based on the ‘shareholder theory’, however, many companies are now moving to corporate governance frameworks based on the ‘stakeholder theory’.

Shareholder theory: The goal of a company is to maximize shareholder returns. The interests of other stakeholders are considered only to the extent that they affect shareholder value.

Stakeholder theory: The company should consider the interests of all stakeholders, not just shareholders. This theory also gives more importance to ESG considerations by making them an explicit objective for the board of directors and management.

We will now look at each stakeholder group in detail.

Shareholders own shares in a corporation and are entitled to certain rights, such as the right to receive dividends and to vote on certain corporate issues.

A shareholder’s interests are typically focused on growth in corporate profitability that maximizes the value of the company.

Banks and Private Lenders

Public Debtholders (Bondholders)

A company’s board of directors is elected by shareholders to protect shareholders’ interests, monitor the company’s operations, and provide strategic direction. The board is also responsible for hiring the CEO and overseeing management performance. A board can be composed on both inside and independent directors.

There is no standard structure or composition for the board of a company. The number of directors can vary depending on the size, structure, and complexity of operations of the company. However, most corporate governance standards require that board members have a diverse range of expertise, backgrounds, and competencies, with at least one-third of the board being independent.

Staggered board is a commonly followed practice, in which directors are divided into three groups and elected into office in consecutive years, so that all directors are not replaced at the same time. The advantage of a staggered board is that it allows for continuous strategy implementation. The disadvantage is that it limits shareholders’ ability to effect an immediate major change in control of the company.

Managers, led by the CEO are responsible for executing the strategy set by the board. They are also in charge of the company’s day to day operations.

Senior managers are typically compensated with a base salary, a short-term cash bonus, and a multi-year incentive plan that includes one or more forms of equity (such as options, time-vested shares, and performance-vested shares). As a result, in addition to acting to protect their employment status, managers may be motivated to maximize the value of their total remuneration.

Lower-level employees seek fair salary, good working conditions, job security, career development opportunities, promotion, etc.

As compared to managers, equity ownership is a minor part of their compensation. Therefore, they are more interested in the company’s long-term stability, survival and growth.

Customers expect to receive products and services of good quality for the price paid. They also expect after-sales service, support, and guarantee/warranty for the period promised. In return, companies strive to keep their customers happy as this has a direct effect on its revenues. Of all the stakeholders, customers are least concerned about a company’s performance.

The primary interest of a supplier is to be paid on time for the products and services delivered to the company. Some suppliers are keen to maintain a good long-term relationship with companies as it is recurring business. Like customers, suppliers typically have an interest in the company’s long-term stability.

Government is a stakeholder as it collects taxes from companies and their employees. Governments seek to protect the interests of the general public and ensure the well-being of their nations’ economies.

A principal-agent relationship arises when a principal hires an agent to carry out a task or a service (e.g. shareholders and managers/directors). An agent is obliged to act in the best interests of the principal and should not have a conflict of interest in performing a task. However, in reality, there are several conflicts of interest that arise in a principal-agent relationship, for example: information asymmetry.

Information asymmetry: Managers have greater access to information about a company’s performance and prospects as compared to outsiders such as shareholders and creditors. This information asymmetry reduces shareholders’ ability to assess managers’ true performance and vote out poor performers. Investors demand higher risk premiums and returns from companies that have greater information asymmetry.

In this section we will discuss a few examples of conflicts between principal-agents and other relationships.

In this relationship, shareholders are the principals and managers/directors are the agents. Compensation is the main tool used to align the interest of managers/directors with those of the shareholders. In theory, stock grants/options offered as part of management compensation are intended to motivate managers to maximize shareholder value. However, in practice, the alignment of interests is rarely perfect. Three common examples of conflict of interests are:

Agency costs: Agency costs arise due to conflicts of interest when an agent makes decisions for a principal. All public companies and large private companies are usually managed by non-owners. Therefore, an agency cost in the context of a corporation is a consequence of a conflict of interest between managers and owners. Since outside shareholders are aware of this conflict, they will take steps that incur costs such as:

The better a company is governed, the lower the agency costs.

Corporate ownership structures can be classified as:

Share ownership alone may not necessarily reflect whether the control of a company is dispersed or concentrated. Controlling shareholders may be either majority shareholders or minority shareholders.

In companies with concentrated ownership, conflict of interest may arise between the controlling and minority (without control) shareholders. For example,

Dual-Share Classes

An equity structure with multiple share classes tends to assign superior voting powers to one class and limited voting rights to other classes. The multiple-class structure allows controlling shareholders avoid dilution of their voting power when new shares are issued and to retain control of board elections, strategic decisions, and all other significant voting matters for an extended period of time — even if their ownership level falls below 50%.

The management of the company is primarily responsible for the operations of a company and has access to all information about the company. Since the board relies on the management for information, its powers and monitoring ability is impacted if information is withheld by the management or only selective information is provided.

There is a conflict of interest between the two suppliers of capital to a company under the following circumstances: