This reading covers:

Common forms of business structures include:

To understand the differences between these business structures we will focus on four areas:

A sole proprietorship is the most basic type of business structure. In a sole proprietorship, the owner personally funds the capital required to operate the business and retains full control over the business’s operations. The owner also fully participates in the financial returns and risks of the business. An example of a sole proprietorship is a family-owned store.

The key features of a sole proprietorship are:

Sole proprietorships are preferred for small scale business due to their simplicity and flexibility. However, their main drawback is that the business is constrained by the owner’s ability to access capital and assume risk.

A general partnership is similar to a sole proprietorship with the important distinction that they have two or more owners called ‘partners’. The roles and responsibilities of partners are outlined in a partnership agreement. As compared to sole proprietorships, this structure allows for additional resources to be brought into the business. The business risk is also distributed among a larger group of individuals. Examples of general partnerships include professional services businesses such as law, accounting, and financial advisory firms.

The key features of a general partnership are:

Like sole proprietorships, the potential for growth for a general partnership is limited by the partners’ ability to source capital, their expertise, as well as their collective risk tolerance.

A limited partnership is a special type of partnership that has at least one ‘general partner’ (GP) with unlimited liability, who is responsible for managing the business. The remaining partners are ‘limited partners’ (LPs) with limited liability i.e., they can only lose up to the amount invested in the business. All partners share profits, with general partners typically getting a larger share. An example of a limited partnership is a private equity fund.

The key features of a limited partnership are:

Business growth is limited by the financing capabilities and risk appetite of the partners. Also, GP’s competence and integrity in running the business affects the business.

A corporation is an evolved model of the limited partnership. It is also called a limited liability company (LLC) or limited company in many countries.

Like a limited partnership, owners in a corporation have limited liability; however, corporations provide greater access to capital and expertise needed to fuel growth. Examples of corporations are national or multinational conglomerates.

The three main types of corporations are:

Nonprofit corporations are formed to promote a public benefit, religious benefit, or charitable mission. They do not have shareholders, do not pay dividends, and generally do not pay taxes. Examples of nonprofits include Harvard university, and the Asian Development Bank.

Most corporations are for-profit. For-profit corporations can be public or private. The main difference between the two are the number of shareholders and whether the shares are listed on a stock exchange. In some countries like the UK, a corporation is categorized as public if the shareholders are greater than 50. While in many other countries, like the US, a corporation is categorized as public if the company shares are listed on an exchange.

We will now discuss the key features of for-profit corporations.

Legal relationship:

A corporation is a legal entity separate and distinct from its owners. Corporations have many of the same rights and responsibilities as an individual. For example, corporations can enter into contracts, hire employees, borrow and lend money, and pay taxes.

Large corporations frequently conduct business in many different geographic regions and are subject to regulatory jurisdictions where either:

Owner-operator separation:

A key feature of corporations is the separation between those who own the business – the shareholders, and those who operate it – the board of directors and company management.

The shareholders elect a board of directors to oversee business operations. The board hires the CEO and senior management for day-to-day operations of the company. This separation of operating control from ownership enables corporations to obtain financing from a large number of investors who are not required to have any expertise in operating the business.

While the board and company management are supposed to act in the best interest of shareholders, conflicts of interest can occur when management places their own interests, or the interests of other stakeholders, above those of the shareholders. To prevent such conflicts and mismanagement of business, corporate governance policies and practices are put in place. If the board or management does not perform as expected, shareholders have the ability to enact change through voting rights attached to their shares. This ability to change things through voting is the key difference between a corporation and a limited partnership.

Business liability:

Owners of a corporation have limited liability. The maximum amount that they can lose is what they invested in the company. Owners also have a residual claim on the company’s net assets after its liabilities have been paid. They can thus participate in the growth of the company.

Capital financing:

The corporate form of business structure is preferred when capital requirements are greater than what could be raised through other business structures. Corporations can raise two types of capital:

Both equity share holders and debt security holders are referred to as investors in the corporation’s securities. However, equity shareholders purchase an ownership stake that entitles them to a residual claim in the corporation. Whereas, bondholders are lenders to the corporation and do not have any ownership entitlement.

Taxation:

In many jurisdictions, corporate profits are taxed twice (double taxation): once at the corporate level and again at the individual level when profits are distributed as dividends to the owners.

Example from the curriculum

The French company Elo (previously known as Auchan Holding) generated operating income of €838 million and paid corporate taxes of €264 million. Investors in France also pay a 30% tax on dividends received. If Elo had distributed all of its after-tax income to investors as a dividend, what would have been the effective tax rate on each euro of operating earnings?

Solution:

| Operating Income | €838 |

| Corporate Taxes (31.5%) | €264 |

| After-Tax Income | (€838 – €264) = €574 |

| Distributed Dividend | €574 |

| Investor Dividend Tax (30%) | €574 × 0.3 = €172.2 |

| Effective Tax Rate | (€264 + €172.2) / €838 = 52.1% |

If the remaining after-tax income of €574 million was paid to investors as a dividend, investors would pay €172.2 million in taxes on the dividends received. Total taxes paid would be €436.2 million (€264 million at the corporate level plus €172.2 million at the personal level), resulting in an effective tax rate of 52.1%.

In this section, we will compare public and private companies with respect to:

Public companies are usually listed on an exchange. This allows ownership to be easily transferred. New investors can become shareholders in a public company by simply executing a buy order. Similarly, exiting investors can liquidate their ownership by executing a sell order. These trades can be executed within a matter of seconds.

Each trade between a buyer and seller can change the share price. We can plot the share price over time to see how the company’s value changes. We can also see how the company’s value is impacted by significant news about the company specifically or about the general state of the economy.

In contrast, private companies are not listed on an exchange, and, therefore have no observable stock price, which makes their valuation challenging. Transactions between buyers and sellers have to be privately negotiated and transferring ownership is much more difficult. Investments in private companies are usually locked up until the company is acquired by another company, or it goes public.

However, the potential returns in private companies can be much larger than public companies. This is because investors in private companies usually join early in the company’s life cycle and they have greater control over management.

Market Capitalization and Enterprise Value

Since the shares of public companies trade on an exchange, we can easily determine what the company’s equity is worth at any moment in time. The company’s market capitalization can be calculated as:

Market Capitalization = Current Stock Price × Total Shares Outstanding

While market capitalization represents the market value of a company’s equity, enterprise value represents the total market value of a company, net of cash held by the company. It is the amount an acquirer will have to pay to own the company free and clear of all debt. Enterprise value is calculated as:

Enterprise Value = Market Value of Shares + Market Value of Debt – Cash

Example from the curriculum

8Tera Therapeutics is a hypothetical, public company with 15.2 million shares outstanding, no short-term debt, and USD200 million of long-term debt. The company also has USD20 million in cash and a recent stock price of USD120 per share.

Solution to 1:

Market Capitalization = Current Stock Price × Total Shares Outstanding

Market Capitalization = (USD120 per share) × (15.2 million shares) = USD1.824 billion

Solution to 2:

Enterprise Value = Market Value of Shares + Market Value of Debt – Cash

EV = USD1.824 billion + USD200 million – USD20 million = USD2.004 billion

Public companies typically raise very large amounts of capital from many investors through an IPO and through additional issues after listing. These investors then actively trade shares among themselves in the secondary market.

In contrast, private companies raise much smaller amounts from far fewer investors who have much longer holding periods.

Investors in private companies are typically invited to purchase shares in the company through a private placement. The terms of private placement are outlined in a legal document called a private placement memorandum (PPM). The PPM describes the business, the terms of the offering, and the risks involved in investing in the company. Because of the higher risks, only accredited investors are permitted to invest in private companies.

Accredited investors are those who are sophisticated enough to take greater risks and to have a reduced need for regulatory oversight and protection. To be considered accredited, an investor must have a certain level of income or net worth or possess a certain amount of professional experience or knowledge.

Registration and Disclosure Requirements

Public companies are subject to greater regulatory and disclosure requirements. They are required to disclose their financial reports as well as other information that may affect stock price, such as – major changes in the holding of voting rights, any stock transactions made by officers and directors etc. These documents are made available to the general public, not just to the company’s investors. The primary purpose of this type of disclosure is to make it easier for investors and analysts to assess the company.

In contrast, private companies are generally not required to make such disclosures and they are not subject to the same level of regulatory oversight.

A private company can go public in the following ways –

Another means of acquisition is through a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC). A SPAC is a shell company, often called a “blank check” company, because it exists solely for the purpose of acquiring an unspecified private company sometime in the future.

SPACs raise capital through IPOs and deposit the proceeds in a trust account. They have a finite time (e.g. 18 months) to complete a deal; otherwise, the proceeds are returned back to the investors.

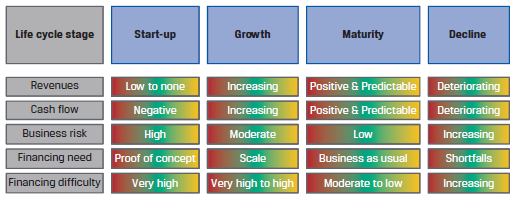

The decision to go public or stay private often depends on where the company is in its life cycle. Companies have a life cycle with four distinct stages: start-up, growth, maturity, and decline. Exhibit 14 from the curriculum depicts the characteristics and financing needs of each stage.

Start-Ups: Start-Ups are initially funded by the founders. If more capital is needed, the founders may reach out to friends and family. At this stage, the company often has very little revenues and negative cash flows. This makes financing challenging.

As the company grows, the founders may hire an investment banker to raise more capital from private equity or private debt investors. Early-stage equity investors are also referred to as venture capitalists, or Series A investors.

Growth: A company needs even more capital to scale in the growth stage. At this stage, the revenue and cash flows of the company increase rapidly. However, the company may still not be profitable, so it cannot rely on internally generated earnings to fund growth. The company may raise capital through a Series B or even a Series C issuance. The company may also consider going public through an IPO.

Maturity: The external financing needs of a company diminishes as it matures. At this stage, a company is usually profitable, generates positive and predictable cash flows and can therefore fund growth internally with retained earnings. If required, the company can also borrow money at reasonable terms from public or private markets.

Decline: A company may have little need for additional financing in the decline stage. At this stage, companies may try to reinvent themselves by developing new products/services or by acquiring other companies. Additional financing may be required to accomplish this, but the financing cost can be expensive as the company’s financials and cash flows deteriorate.

Public to Private — LBO, MBO

Some public companies may also choose to go private. To accomplish this an investor has to acquire all of the company’s shares and delist it from the exchange. The process usually involves borrowing large amounts of money to finance the acquisition (buyout). Buyouts can be classified as:

LBOs and MBOs are initiated when investors believe that the public market is undervaluing the shares and when financing costs are sufficiently low to make such transactions attractive.

Trends in Public and Private Companies

The number of public companies is increasing in many emerging economies, while it is decreasing in many developed economies.

Emerging economies usually have higher growth rates and are transitioning from closed to open market structures. Therefore, the number of public companies are increasing as these economies grow larger.

In developed economies, the number of public companies is trending downwards because:

The key differences between debt and equity financing are:

Investor’s perspective

From an investor’s perspective, investing in equity is riskier than investing in debt. Debtholders receive predictable coupon payments, whereas payments to shareholders are at the company’s discretion.

However, equityholders do have a residual claim, which means they are entitled to whatever firm value remains after other stakeholders have been paid off, giving them unlimited upside potential. Therefore, equityholders have an interest in the ongoing maximization of company value (net assets less liabilities), which directly corresponds to the value of their shareholder wealth.

On the other hand, no matter how profitable a company becomes, debtholders will never receive more than their interest and principal repayment. Their maximum return is capped. They are therefore interested in assessing the likelihood of timely debt repayment and the risk associated with the company’s ability to meet its debt obligations.

For both equityholders and debtholders, their initial investment represents their maximum possible loss.

These points are summarized in the table below:

| Investor Perspective | Equity | Debt |

| Return potential | Unlimited | Capped |

| Maximum loss | Initial investment | Initial investment |

| Investment risk | Higher | Lower |

| Investment interest | Max (Net assets – Liabilities) | Timely repayment |

Issuer Perspective

From the company’s perspective, issuing debt is riskier than issuing equity. If a company fails to meet its contractual obligations, it may be forced to declare bankruptcy and liquidate.

Although riskier, the cost of debt is lower than the cost of equity (this is because the returns to debtholders are capped). A company generating stable, predictable cash flows generally prefers to borrow money rather than issuing additional equity to raise capital. Issuing more equity also dilutes the upside return for existing equity owners given that residual value must be shared across more owners. However, early-stage companies or companies with unpredictable cash flows that find it difficult to borrow may prefer to raise capital through equity to avoid the risk of default.

In the event of a default, a company does have some options to try and avoid bankruptcy. It can renegotiate more favorable terms with the debtholders. However, if things don’t improve, eventually the assets may have to be liquidated to raise as much money as possible to return to the bondholders. Alternatively, the company may be reorganized, with existing shareholders getting wiped out and bondholders becoming the new shareholders of the reorganized company.

These points are summarized in the table below:

| Issuer Perspective | Equity | Debt |

| Capital cost | Higher | Lower |

| Attractiveness | Creates dilution, may be only option when issuer cash flows are absent or unpredictable | Preferred when issuer cash flows are predictable |

| Investment risk | Lower, holders cannot force liquidation | Higher, adds leverage risk |

Potential conflicts of interest can occur between debtholders and equityholders. Debtholders would prefer that the company invests in less risky projects that generate predictable cash flows, even if those cash flows are relatively small. Equityholders, on the other hand, would prefer that the company invests in riskier projects with a much higher return potential.