This reading covers:

A well-defined business model helps analysts in understanding a company’s operations, strategy, target customers, key partners, prospects, risks, and financial profile. Many companies have conventional business models that are easily understood, such as manufacturer, wholesaler, retailer, restaurant chain etc.

However , the advent of digital technology has changed the way most businesses operate, and enabled disruption of existing business models. Many companies now have business models that are complex, specialized, or new.

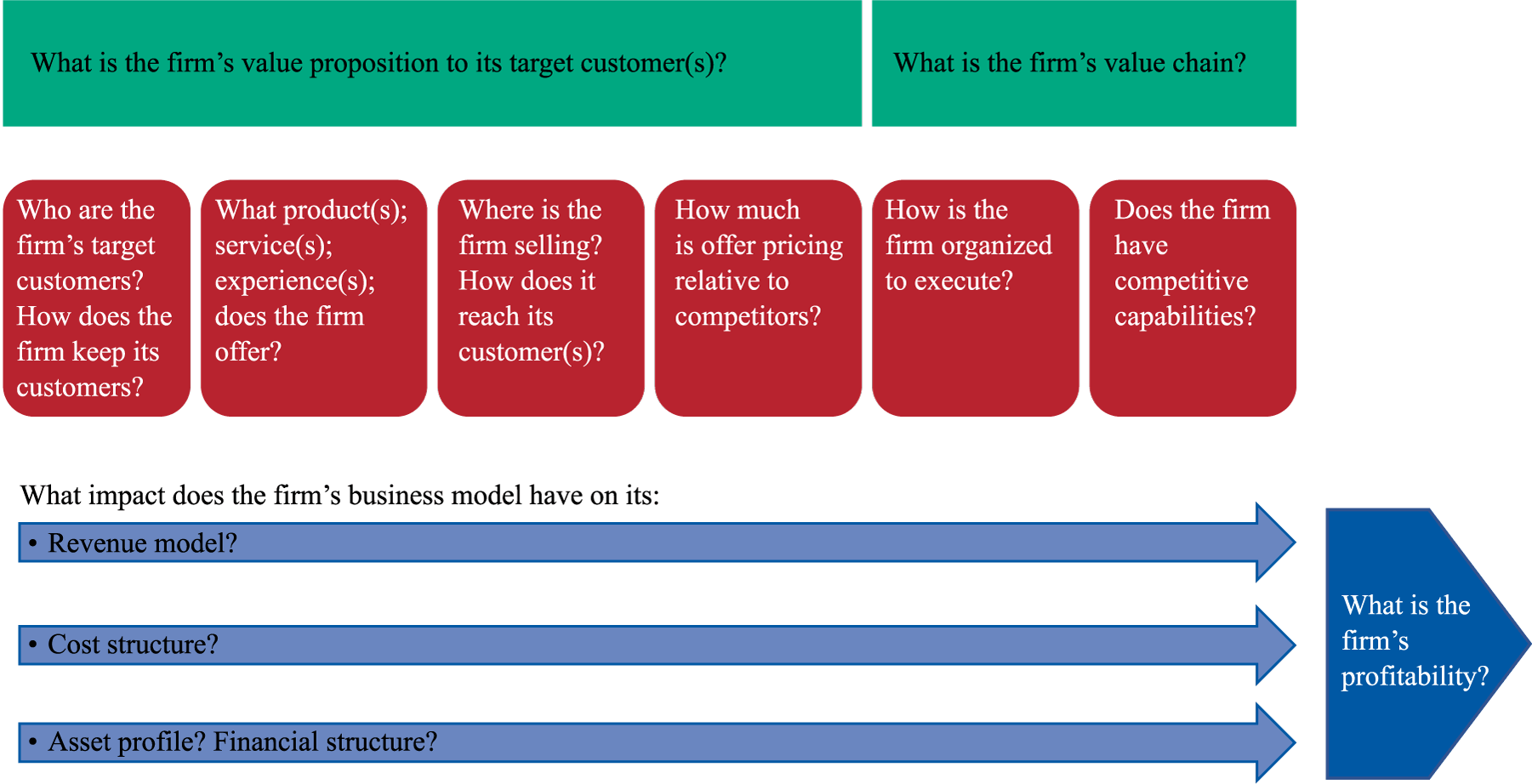

A business model describes how a business is organized to deliver value to its customers:

A business model explains what the company does, how it operates, and how it generates revenue and profits, as well as how it differs from competitors. It provides enough detail to understand the basic relationships between these key elements, however, it does not provide a full description. For a full description (such as detailed financial forecasts) we would have to refer to a business plan.

A business model should have a value proposition and a value chain.

This is illustrated in Exhibit 1 from the curriculum.

The key features of a public company’s business model are often provided in annual reports or other disclosure documents. As an example, the curriculum presents the ‘business description’ from Tesla’s annual report.

“We design, develop, manufacture, sell and lease high-performance fully electric vehicles and energy generation and storage systems, and offer services related to our products. We are the world’s first vertically integrated sustainable energy company, offering end-to-end clean energy products, including generation, storage and consumption. We generally sell our products directly to customers, including through our website and retail locations. We also continue to grow our customer-facing infrastructure through a global network of vehicle service centers, Mobile Service technicians, body shops, Supercharger stations and Destination Chargers to accelerate the widespread adoption of our products. We emphasize performance, attractive styling and the safety of our users and workforce in the design and manufacture of our products, and are continuing to develop full self-driving technology for improved safety. We also strive to lower the cost of ownership for our customers through continuous efforts to reduce manufacturing costs and by offering financial services tailored to our vehicles. Our sustainable energy products, engineering expertise, intense focus to accelerate the world’s transition to sustainable energy and achieve the benefits of autonomous driving, and business model differentiate us from other companies.”

In this paragraph, Tesla describes many features, including its products and their attributes, key channels, and its emphasis on innovation and vertical integration. Let’s take a closer look at the features.

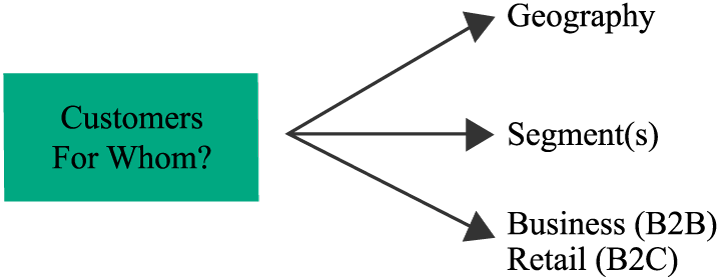

A business model should identify the firm’s target customers:

In the Tesla example, the business description does not specify which customer segments are being targeted. This is most likely because Tesla’s target market is shifting over time toward the mass market, as costs and prices decline.

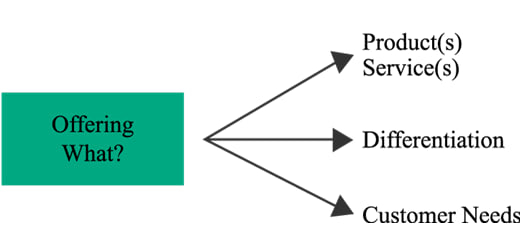

A business model should define:

In the Tesla example, instead of using a broad description such as “electric car” to describe its product offering; Tesla has used a more precise description that is useful to analysts – “high-performance fully electric vehicles and energy generation and storage systems”.

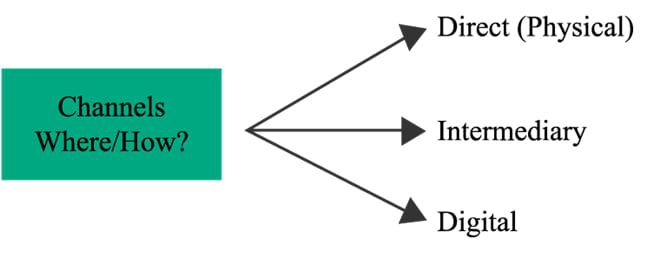

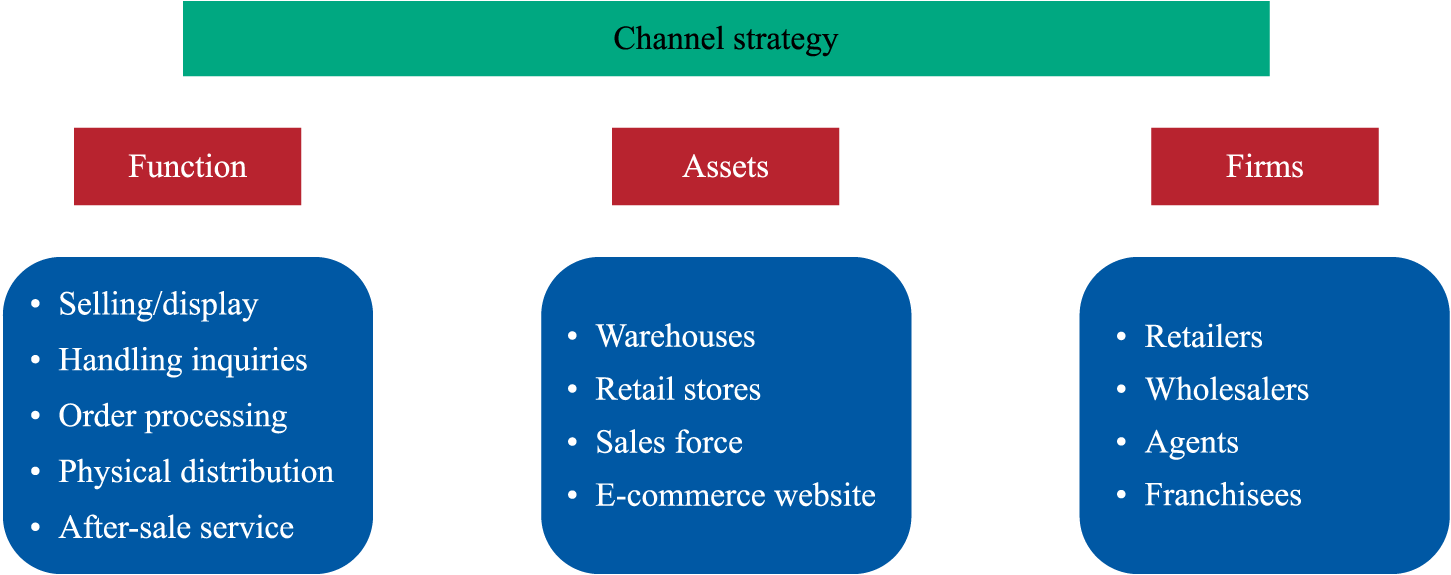

A firm’s channel strategy refers to “where” the firm is selling its offering and how it is reaching its customers. Channel strategy typically involves two main functions:

When evaluating a firm’s channel strategy, it is important to distinguish the functions performed, from the assets that might be involved, and different firms that might be involved in performing those functions or owning those facilities. Exhibit 2 from the curriculum, illustrates this concept.

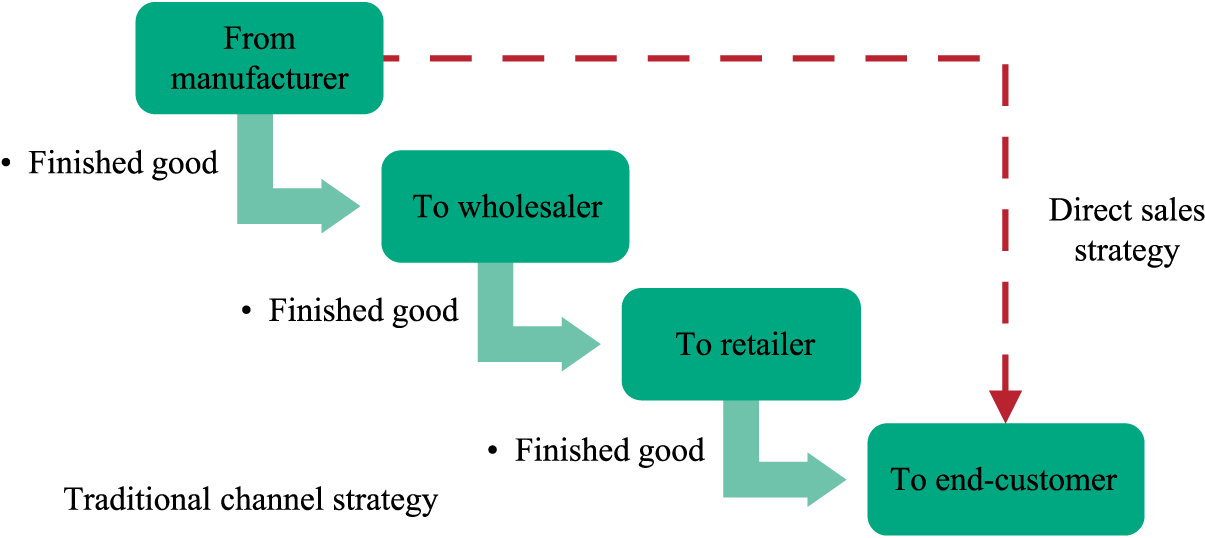

Many “product” businesses, employ a traditional channel strategy, that reflects the flow of finished goods (e.g., from manufacturer to wholesaler, retailer, and end customer). However, some manufacturers may employ a direct sales strategy, selling directly to the end customer. This strategy bypasses (or disintermediates) the distributor and retailer. Typically, direct sales involved the use of the company’s own sales force and was very expensive. However, with e-commerce, direct sales have now become a cost-effective strategy. Exhibit 3 from the curriculum compares the two strategies.

When an intermediary is involved, that intermediary may work on an agency basis, earning commissions, rather than taking ownership of the goods (e.g., auctioneers such as Sotheby’s that deal in fine art).

The drop shipping model in e-commerce allows an online marketer to have goods delivered directly from the manufacturer to the end customer without taking the goods into inventory.

Companies often use several channels in tandem. With an omnichannel strategy, both digital and physical channels are used to complete a sale. For example, a customer might order an item online and pick it up in a store (“click and collect”).

It is important to understand how a firm’s channel strategy differs from those of its competitors. For example, Tesla mentions its direct sales strategy, which differs from the franchised dealer model used by most automakers.

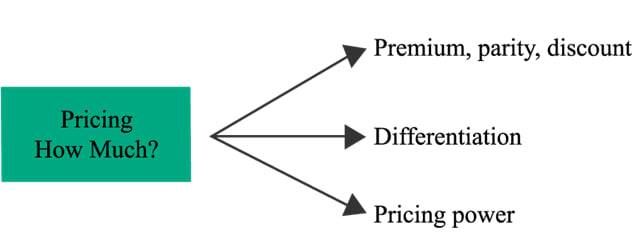

A business model should answer the following questions related to pricing:

Based on pricing power companies can be classified into:

Most firms try to differentiate their offerings in some way to achieve some degree of pricing power. For example, Tesla focuses on the “total cost of ownership” which factors in government subsidies and lower operating costs for electric vehicles as an offset to higher purchase prices.

Pricing and Revenue Models

Pricing approaches are typically value based or cost based.

Price Discrimination

Price discrimination refers to situations where firms charge different prices to different customers. The objective of price discrimination is to maximize revenues in a situation where different customers have different willingness to pay. Common pricing strategies in this category include:

Pricing for Multiple Products

Firms selling multiple products frequently use the following pricing models:

Pricing for Rapid Growth

Alternatives to Ownership

Some business models create value by offering an alternative to purchasing an asset or product, such as:

A firm’s value proposition refers to the product or service attributes valued by a firm’s target customer that lead those customers to prefer a firm’s offering over those of its competitors, given relative pricing.

Value propositions can arise from:

In the Tesla example, its electric car value proposition highlights the advantages of its electric propulsion system: zero emissions and high performance (strong and silent acceleration) and technological sophistication (e.g., self-driving capabilities, frequent enhancements via software upgrades).

In addition to specifying a firm’s value proposition, a business model should also specify “how” the firm is structured to deliver that value. It should address the following questions:

Value Chain

The “how” aspect of a business model is also referred to as a firm’s value chain. It refers to the systems and processes within a firm that create value for its customers.

A value chain includes only those functions performed by a single firm. Some of these functions may be valued by customers but may not involve physical transformation or handling the product.

A firm’s value chain is different from a supply chain. A supply chain refers to the sequence of processes involved in the creation of a product, both within and external to a firm. It includes all steps involved in producing and delivering a product, regardless of whether those steps are performed by a single firm.

Value chain analysis provides a link between the firm’s value proposition for customers and its profitability. It involves:

A business model should specify how the firm expects to generate its profits. To understand the profitability of a business, the analyst should examine margins, break-even points and unit economics (which is expressing revenues and costs on a per-unit basis).

The curriculum provides the following examples for unit economics:

Example:

A producer of bottle caps might sell its product at 2.5 cents per unit, with direct costs for material and labor of 2.0 cents per unit and a contribution margin (selling price per unit minus variable cost per unit) of 0.5 cents per unit. If the firm has fixed costs of USD500,000 per year, what is its unit break-even point?

Solution:

Break-even point (unit) = Fixed costs/Contribution margin

= USD500,000/0.5 cents

= 100 million units.

Example:

A restaurant chain might have an average order of EUR50, with ingredient costs equal to 50% of sales. If fixed costs are EUR250,000 annually per outlet, what is the firm’s unit break-even point and operating margin at 20,000 orders per year?

Solution:

Break-even point (order) = Fixed costs/Contribution margin

= EUR250,000/EUR25

= 10,000 orders/year.

Operating margin = 20,000 orders × EUR50

= EUR1,000,000 revenues – EUR500,000 ingredient costs (50% of sales) – EUR250,000 fixed costs

= EUR250,000 operating profit, or

= EUR250,000/EUR1,000,000 = 25%.

Tesla’s business model is based on declining unit revenues and costs over time as volume increases and technology improves. This is expected to result in a virtuous circle: Lower prices allow Tesla to expand its addressable market and market share, while lower costs allow profits to rise and create a competitive barrier.

Each industry tends to has its own set of established business models. Firms in the goods-producing sectors are generally easy to classify based on how they fit into the supply chain. For example, manufactures, wholesalers, retailers, suppliers etc.

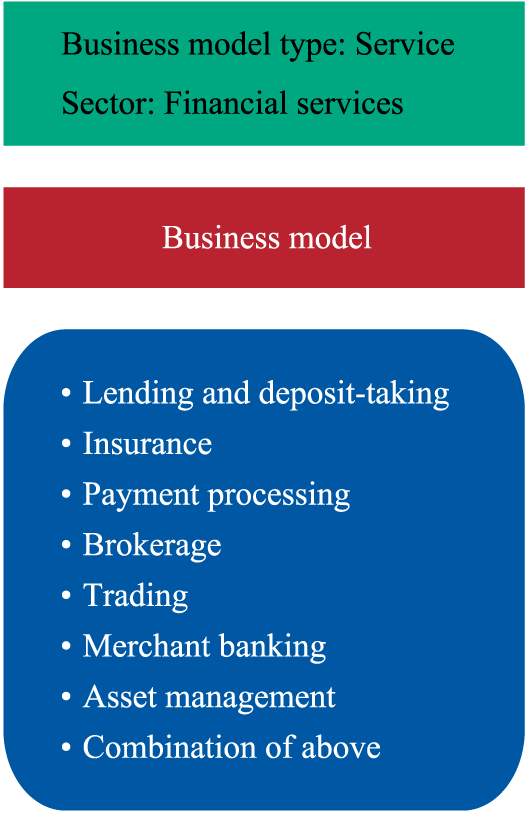

However, service businesses are more diverse. For example, the financial services sector has many established business models, as shown in Exhibit 5.

Some firms combine these models together (e.g. universal banks) while some specialize in a particular model (e.g. discount brokers).

Digital technology has transformed the “where” and “how” elements of business models in established markets, by drastically reducing the cost of communicating, exchanging information, and transacting between businesses.

There are many business model variations such as:

E-commerce is a broad category that includes a wide range of internet-based direct sales models. A few key variations of e-commerce business models include:

The term “network effects” refers to the increase in value of a network to its users as more people join. Many internet-based businesses are built on network effects. For example, social media, ride-sharing services, online classified etc. Network effects are also applicable to older, non-internet businesses such as telephone services, credit cards etc.

Network effects can be described as:

A platform business is defined as a business based on network effects—that is, where the value of its service or product is enhanced by the addition of customers or users. They are different from traditional or linear businesses. With a linear business, value is added by the firm; with a platform business, value is created in the network, outside the firm.

Crowdsourcing business models enable users to contribute directly to a product, service, or online content. For example, Wikipedia, Google Maps, Tripadvisor.

Some companies employ hybrid models that combine platform and traditional “linear” businesses. For example, Tesla sells cars via a linear model, but its customers benefit from an expanding network of charging stations.

Businesses have very different financing needs and risk profiles depending on both external and firm specific factors. These factors influence the firm’s ability to raise capital.

External factors include:

Firm-specific factors include:

Financial analyst and investors must consider risk factors that can cause investment returns to be different from expectations. Risk can be categorized into:

Macro risk refers to the risk from political, economic, legal, and other institutional risk factors that impact all businesses in an economy, a country, or a region. The primary macro risk affecting most businesses is the potential slowdown or decline in economic activity. Depending on its geographic location, other country risk factors such as exchange rates, political instability, or gaps in the legal framework may also be important for a business. Some business such as consumer staples are less sensitive to economic activity, whereas, others such as capital goods are more sensitive.

Business risk is the risk that the firm’s operating results will be different from expectations, independently of how the business is financed. In accounting terms, we can say that business risk reflects the risk at the operating profit (EBIT) level. EBIT can be lower than expected due to lower revenues and/or higher than expected costs.

Financial risk refers to the risk arising from a company’s capital structure, specifically from the level of debt and debt-like obligations (such as leases and pension obligations) involving fixed contractual payments. Debt(financial leverage) causes net profit to vary more than operating profit, on both the upside and downside.

The impact of risks on a business are cumulative. A company’s operating results are affected by both macro risks and business risks. Likewise, a company’s net earnings reflect the combined impacts of macro risks, business risks and financial leverage.

Industry risks apply to all companies in the same industry and include risk factors that are likely to affect the industry’s overall level of demand, pricing, and profitability.

Firms try to reduce the impact of cyclicality in different ways:

Cyclical firms tend to have more conservative capital structure policies, with little debt as compared to less cyclical firms.

The Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (HHI) is frequently used to measure industry concentration. It is calculated by squaring the market share of each firm competing in a market and then summing the resulting numbers. High numbers indicate high concentration and vice-versa.

It is important to define the industry appropriately. If an analyst defines an industry too broadly, then conclusions drawn from the industry analysis may be too broad to be useful.

In general, a narrower industry definition is preferable. However, defining the industry too narrowly can make it difficult to obtain accurate data on demand and competition and to draw conclusions about risk factors affecting the industry as a whole.

Company-specific risk vary based on the nature, scale and maturity of the business. They can be categorized into:

The typical sources of competitive advantage are:

The larger and more durable these advantages, the lower the level of competitive risk.

Competitive risk can also arise from “disruption”, where new competitors use new technology or business models to take market share from existing firms.

Instructor’s Note: This topic is covered in detail in a separate reading.

Financial risk refers to the risk arising from a company’s capital structure, specifically from the level of debt and debt-like obligations (such as leases and pension obligations) involving fixed contractual payments. Debt(financial leverage) causes net profit to vary more than operating profit, on both the upside and downside.

High financial leverage increases the probability that the firm will be unable to secure needed financing (financing risk) or that it will fail to meet its financial obligations (default risk).

Financial risk reflects the cumulative impact of macro and business risk.

Different businesses can support different levels of financial leverage. Businesses with stable and predictable cash flows can generally support a high level of financial leverage. For example, an electric utility company.

Leverage is the use of fixed costs in a company’s cost structure. It has two components:

For highly leveraged firms, i.e., firms with a high proportion of fixed costs relative to total costs, a small change in sales will have a big impact on earnings.

Operating leverage captures the sensitivity of operating profit (EBIT) to changes in revenue. It can be calculated as:

Operating leverage = Contribution/EBIT

where: Contribution = Sales – Variable costs

Financial leverage captures the sensitivity of net profit to a change in operating profit. Earnings before taxes (EBT) are frequently used instead of net profit, because taxes fluctuate. Therefore, financial leverage can be calculated as:

Financial leverage = EBIT/EBT

The total leverage of the company can be expressed as:

Total leverage = Operating leverage × Financial leverage